Temporal arteritis is a commonly used term that refers to an inflammation of the temporal artery. There is some confusion about terminology since this entity is also referred to as giant cell arteritis. This latter term describes the pathologic appearance inflamed arteries—infiltrated by multinucleated giant cells as well as lymphocytes and plasma cells.

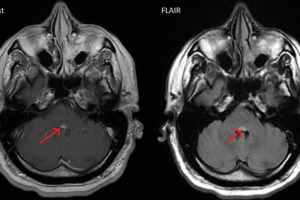

This entity represents an opthomological emergency, and if the central retinal artery becomes involved, almost half of cases involve loss of eye sight. It should be considered in any patient over the age of 50 with temporal headaches. The primary abnormality appears to be a cell-mediated response against antigens associated with the elastic component of the vascular wall. These reactions are also seen in other conditions with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) being the most common.

In general, the incidence of visual involvement is high with 50% to 60% of patients losing vision if not treated. Further, three quarters of patients who have unilateral symptoms will have bilateral symptoms within 3 weeks.

This is a disease that rarely occurs in patients younger than 50 years. Mean onset is age 70. Headache is the most common presenting complaint. It is typically characterized as being “different,” but there is rarely anything else remarkable about its character. Pain is most often unilateral although not always. It is also usually in the temporal region but this too can vary. Its onset may be insidious, and it gradually worsens. As the pain progresses, it often takes on an ever increasing surface character.

There is also a significant proportion of patients who present just with visual complaints. Onset of these symptoms may be sudden and painless. Vision loss may be of the amaurosis fugax-type, i.e. transient, or, unfortunately, it may be permanent. Because of the proximity of the tempero-mandibular joint, jaw claudication may occur, occurring in approximately 65% of patients when they are chewing. Systemic complaints may include anorexia and weight loss, fatigue, sweats, malaise, fatigue, and depression.

There is no one single test that confirms a diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology established criteria for diagnosing the disease that consists of having 3 of the following 5 conditions: older than 50, new onset of headache, temporal artery tenderness, decreased pulsations not related to arteriosclerosis of cervical arteries, Westergren erythrocyte sedimentation rate (WESR) greater than 50 mm/h.

Physical examination should include close attention to the head and neck. The temporal artery should be checked for tenderness, heat, and decreased pulse. Sometimes, the artery may actually have thickened to a point where it can be rolled between two fingers. The scalp should be checked for nodules or sclerotic areas. A full neurologic should include visual acuity, visual fields, cranial nerve exam (with close attention to the sixth looking for a palsy), and a slit lamp exam. The fundus should be checked for findings compatible with the disease which include a pale optic disc, a retina with cotton wool patches, or beaded retinal veins.

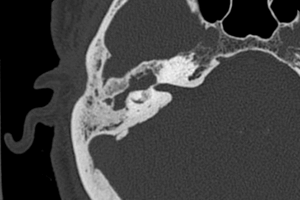

Diagnosis of temporal arteritis can me initially made clinically, but should be verified by temporal artery biopsy. Temporal arteries that have no tenderness or swelling may still prove to be abnormal on biopsy. However, because vasculitis is segmental, bilateral biopsy of greater than 2 segments on each side is recommended for maximum confirmation. Angiography may sometimes demonstrate arterial narrowing in patients with pulse deficits. Also, lab studies may reveal elevated serum alkaline phosphatase as well as a polyclonal hyperglobulinemia.

Because of the possibility of vision loss, treatment should never be delayed pending biopsy results. Prednisone at a dose of 60 mg per day should be initiated, to be gradually tapered depending upon patient response. The ESR is not a good parameter to use for gauging treatment response. Clinical course is better—surging steroids slightly if symptoms worsen.