Optic neuritis is inflammation of the optic nerve. It is principally due to demyelinization and is closely associated with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Potential etiologies of optic neuritis

Almost one fifth of new cases of MS present as an optic neuritis. Studies estimate that 40% to 50% of MS patients will eventually develop an optic neuritis.

Neuromyelitis optica (Devic disease) is another demyelinating process affecting the optic nerve that is often misdiagnosed as MS. Devic’s disease affects the optic nerves and the spinal cord but more often spares the brain. While NMO is also a demyelinating autoimmune disease the etiology, pathophysiology and treatment is completely different from MS.

Processes causing optic neuritis other than demyelinization include Lyme disease, tuberculosis, syphilis, and viral agents such as HIV, hepatitis B virus, herpes virus, and cytomegalovirus, paranasal sinus infection, radiation therapy, giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis), and rarely some drugs.

Clinical presentation of optic neuritis

Clinical presentation of optic neuritis has been described as having a classic triad of vision loss, eye pain, and impairment of accurate color vision. The progression of events is gradual with both vision and pain worsening over a course of days to weeks. Recovery is usually spontaneous with restoration of vision loss beginning within 2 to 3 weeks and stabilizing over months.

There are some unusual clinical manifestations of inflamed optic nerves. These include movement or sound induced brief flashes of light (phosphenes) that last for a few seconds and in 50% of patients, an exercise or heat induced loss of vision called the Uhthoff symptom. Vision may also paradoxically get worse in bright vision.

In children, optic neuritis is typically related to infectious episodes and much less likely to herald the appearance of MS.

Permanent nerve damage occurs in roughly 80% of patients, but usually this damage is subclinical. These subclinical cases may actually be discovered coincidentally during an examination for MS, particularly during electrophysiological visual-evoked exams.

Within 5 to 10 years, perhaps a quarter of patients have a re-occurrence of the neuritis—in the same or sometimes in the contralateral eye. Intravenous methylprednisolone has been demonstrated to accelerate the rate of recovery, but it does not improve long term vision recovery. Thus, corticosteroids are not recommended other than in classes of patients where immediate recovery is crucial, e.g., monocular patients or those whose occupations require excellent visual acuity.

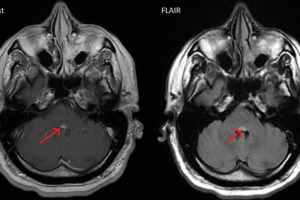

Another class of patients where steroids and/or immunomodulation, such as interferon beta-1a, interferon beta-1b, glatiramer acetate, should be considered are those that are at risk for multiple sclerosis. Use of brain MRI is used to define this population, looking for brain lesions.

Diagnosis of causes of optic neuritis

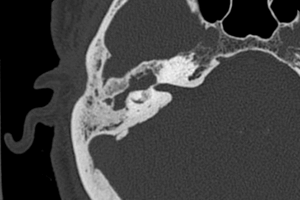

When there is confusing data or in the case of an atypical presentation, MRI is helpful in excluding other diagnoses. Intravenous contrast enhances the visualization of high-signal intensity foci in a minimally or non-expanded nerve—not normally seen in a healthy nerve.

However, MRI is still of the most crucial use when evaluating for the possibility of multiple sclerosis, i.e. looking for white matter lesions. These studies also play a significant role in treatment in that it has been shown that in 2-year followups of patients with optic neuritis and 2 or more brain lesions on MRI, intravenous methylprednisolone therapy group showed a significantly decreased risk of developing multiple sclerosis.

Head CT, however, plays little role in the evaluation of optic neuritis.