As a complaint, dizziness and vertigo are as common as back pain and headache. Any seasoned primary care physician will testify to the difficulties posed by dizzy patients. They can be both frustrating and confusing, and a patient who is dizzy and tired represents the iconic test of a practitioner’s patience.

A systematic approach to dizziness

However, even the morass of dizziness is less exasperating when approached systematically with careful attention to carving out important historical details and applying an understanding of inner ear, visual, proprioceptive, and cerebellar function to the data gained from a careful physical exam. This allows a practitioner to place patients into at least broad categories with regard to causes for their complaints.

It is also much more intellectually honest than immediately sending all dizzy patients to ENT specialists. All they will do is induce vomiting by squirting ice water into your patient’s ears and then return them to your practice with a sheet of vestibular exercises.

One of those most difficult parts of evaluating the problem is wrapping one’s arms around exactly what a patient is describing. Specifically, does the patient mean vertigo, unsteadiness, generalized weakness, syncope, presyncope, or falling?

Differentiating between vertigo and nonvertigo is critical. Vertigo is the sensation of true rotational motion—the world spinning or the patient spinning within the world. Nonvertigo involves the sensations of light-headedness, unsteadiness, motion intolerance, imbalance, floating, or a tilting sensation. Making this distinction is important because true vertigo is most commonly related to inner ear disease or problems central vestibular projections while nonvertigo is engendered by cardiovascular or systemic diseases. It is also true that inner ear episodes are recalled as sudden onset episodes while episodes caused by CNS, cardiac, and systemic diseases are less well defined.

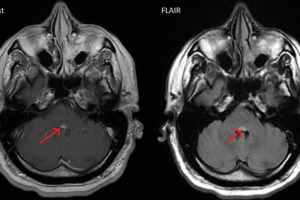

True vertigo that is brief and associated with changes in head or body position is probably due to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). True vertigo that lasts longer, days or weeks, is probably from Ménière’s disease (especially if associated with hearing loss and tinnitus) or vestibular neuronitis. Vertigo of sudden onset that lasts for minutes can be due to brain or vascular disease, especially if cerebrovascular risk factors are present. The vertigo that is secondary to brainstem or cerebellar ischemia is often associated with diplopia, nausea, dysarthria, dysphagia, or focal weakness. Vertigo can also be associated with migraine headaches.

Ataxia is most commonly caused by cerebellar disease. Sensory and motor symptoms, memory dysfunction, and personality change are usually associated with CNS diseases.

When taking a history, an examiner should also do a complete review of systems, screening for anxiety and/or depression, history of prescription medicines, over-the-counter medications, herbal medicines, and recreational drugs. Pharmacological syndromes are a common cause of dizziness.

The physical exam for dizziness

A careful physical examination can be crucial in sorting through what may appear to be a confusing picture.

The ears should be examined for signs of cerumen impaction, external otitis, otitis media, and masses. Hearing can be tested through confrontational whispering and with the use of tuning forks.

Eye movements should be checked for the presence of spontaneous nystagmus, gaze-evoked nystagmus or ocular-motor abnormalities. Nystagmus, whether it is spontaneous, gaze induced, or positional, must be completely characterized.

Vertigo that is central is not suppressed by visual fixation. Peripheral vertigo is typically rotatory. It is accelerated by removing visual fixation, and the intensity of nystagmus increases when gaze moves in the direction of the fast phase of the nystagmus (Alexander law).

An intact oculocephalic reflex and intact dynamic visual acuity are indications of good vestibular function.

Another important test of vestibular function is the failure of fixation suppression test. Failure of fixation suppression (FFS) tests cerebellar modulation of vestibular reflexes. FFS is defined as nystagmus that occurs during en bloc head and trunk rotation while the patient fixates on outstretched arms with his or her hands clasped together—rather like an ice skater spinning, while pointing at the audience, hands held together.

There are a number of other positioning tests including the Dix-Hallpike test, testing of the vestibulospinal reflexes through the Romberg and Fukuda tests, the Hamid vestibular stress test, and caloric testing. These tests are usually performed in the office of an otologist, particular caloric testing, which has been described as “water-boarding of the inner ear.”

There is one test that primary care specialists should use whenever it comes to mind. It tests for a syndrome that is far more common than is appreciated—hyperventilation syndrome. Patients should be placed in a seated position and instructed to hyperventilate. Examiners monitor the hyperventilation for two minutes while also watching for signs of nystagmus. This is best done with Frenzel goggles or an infrared video system, but gross observation will suffice if these are not available.

If the test reveals nystagmus or if the patient describes that it has recreated the sense of dizziness, it is quite possible that subtle hyperventilation is causing the dizziness. Hyperventilation may be so subtle as to not be evident, but it accentuates both peripheral and central vestibular dysfunction.

This dysfunction may simply be normal variation in which case it is the hyperventilation itself that is causing the problem. It may also be a subclinical abnormality, but the isolation of such a clinical trigger can prove to be of great value.

A differential diagnosis for dizziness

The differential diagnosis for dizziness should first be categorized into vertiginous and non-vertiginous “dizziness.”

Vertigo can be further subcategorized into PERIPHERAL and CENTRAL.

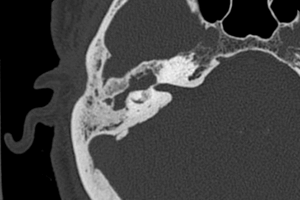

Peripheral causes of vertigo include acute vestibular neuronitis, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), Meniere’s Disease, serous otitis media, chronic otitis media, otitis externa, mastoiditis, Ramsay Hunt Syndrome (herpes zoster oticus), acute labyrinthitis (both viral and bacterial, and both very rare), cholesteatoma, perilymphatic fistula, otosclerosis, temporal bone fracture, and labyrinthian concussion.

Central causes of vertigo include acoustic neuroma (vestibular schwannoma), infratentorial ependymoma, brainstem glioma, medulloblastoma, neurofibramatosis, migraine headache, multiple sclerosis, brainstem infarcts (from strokes and TIAs), anxiety, and depression.

Nonvertigo can be further subcategorized into PRESYNCOPE and DYSEQUILIBRIUM.

Presyncopal types of dizziness include vasovagal syncope, micturation syncope, cough syncope, hyperventilation, carotid sinus syncope, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, TIA, seizures, ventricular tachycardia, sick sinus syndrome, supraventricular tachycardia, atrioventricular block, pacemaker dysfunction, aortic stenosis, mitral stenosis, myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, subclavian steal syndrome, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial myxoma, and medication effect including beta blockers, opthalmic beta blockers, nitrates, digitalis, antiarrhythmic medications (particularly Type 1a), diuretics, adriamycin, phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, recreational drugs including alcohol, ectasy, and methamphetamines.

Dizziness reflected as disequilibrium can be caused by motion sickness, alcoholism, vitamin B12 deficiency, diabetes mellitus, visual defect, autoimmune disease, tertiary syphilis, anxiety, panic disorder, and depression.