Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is an entity often confused with vestibular neuronitis (VN). It is, however, clinically and pathophysiologically distinct, and it should be relatively easy to distinguish between the two.

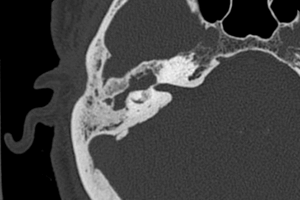

They are similar in that they are characterized by short-lived episodes of vertigo in association with rapid changes in head position. However, BPPV is caused by pathology in the posterior semicircular canal of the inner ear. VN is a lesion in the vestibular nerve and probably related, in some fashion, to an infectious etiology.

It is now believed that benign positional vertigo is caused by “canalolithiasis.” This is a process wherein free floating debris in the endolymph of the semicircular canal causes continuing stimulation of the auditory canal for several seconds after movement has ceased. Sometimes, the onset of this problem can be associated with mild head trauma. More often, it is considered to be idiopathic. It can occur at any age but is more common in the sixth and seventh decades.

The vertigo associated with BPPV lasts from a few seconds to a minute. Sitting up or lying down in bed or turning to reach for objects on high shelves are common activities that precipitate an attack. When the disease is active, attacks tend to cluster together. After periods of remission, symptoms can reoccur.

The test used to confirm the diagnosis of BPPV is the Hallpike manoeuvre. A patient is rapidly moved from the seated to lying position with his or her head tipped below the horizontal plane, 45 degrees to the side, and with the affected side downwards. A positive test is the production of vertigo and nystagmus.

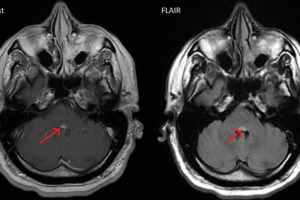

The rotatory nystagmus typically has a latency of a few seconds before onset and fatigues after 30-40 seconds. The key factor here is that there is nystagmus accompanying the maneuver. VN is not accompanied by nystagmus. Patients who develop symptoms but do not have nystagmus do not have BPPV.

However, patients who have vertigo due to pathology in the central nervous system may develop nystagmus with the Hallpike maneuver. But this nystagmus usually has no latent period, the nystagmus does not fatigue with time or repeated testing, and there is usually not an accompanying nausea.

Fortunately for patients who suffer with this problem, there is a form of physical therapy called “repositioning” that uses head movements to manipulate the labyrinthine debris such that it no longer causes vertigo. There have now been a number of studies that have elevated this treatment beyond the nature of one supported only by word of mouth.

The best known of these treatments is the Epley procedure—best demonstrated rather than described.