Acoustic neuromas (more properly called vestibular schwannomas) arise from the Schwann cell sheath of either the vestibular or the cochlear nerve. They account for four-fifths of cerebellopontine angle tumors (the remaining 20% are mostly meningiomas.) Most of the schwannomas are derived from the vestibular portion of the vestibulocochlear nerve. Less than 5% arise from the cochlear nerve. Most acoustic neuromas grow slowly, but some grow quite quickly, doubling within 6 months to a year. Some tumors alternate between rapid and slow growth patterns.

Because a vestibular schwannoma arises from cells on the outside of nerves, as they grow, it compresses and destroys vestibular fibers, but destruction is slow. Once the internal auditory canal is filled with tumor, it may continue to grow. It then either erodes bone, or tumor spills into the cerebellopontine angle.

Tumor creates symptoms by symptoms compression or distortion of the spinal fluid spaces, displacement of the brain stem, compression of vessels producing venous or arterial infarction, or compression of nerves. The cerebellopontine angle is relatively empty, and this allows tumor to grow until they reach the size of 3-4 cm. Growth is slow enough that the facial nerve may be able stretch with the growth without experiencing dysfunction.

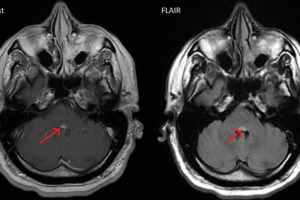

Any unilateral sensorineural hearing loss must be considered to be an acoustic neuroma until proven otherwise. Because of direct injury to cranial nerve VIII, many patients will have decreased speech discrimination scores out of proportion to the reduction in the pure-tone average, something typical for retrocochlear lesions. Hearing loss may be sudden or fluctuating. 3% to 5% of cases will have normal hearing at the time of diagnosis. Surprisingly, medium and large tumors are nearly as likely to have normal hearing very small tumors. Discovery of tumors through the use of gadolinium-enhanced MRI is common. By itself, the presence of unilateral tinnitus should institute workup an acoustic tumor.

Vertigo and dysequilibrium are uncommon presenting symptoms. Overall, if carefully questioned, approximately 40-50% of patients with acoustic tumors report some balance disturbance. Headaches are present in about half of patients, only a tenth of patients identify headache as a presenting complaint. A quarter of patients present with facial numbness. Facial weakness is uncommon.

Clinical guidelines suggest that all patients with unilateral or asymmetrical hearing symptoms have a pure tone audiogram, appropriately masked as necessary. Speech discrimination eudiometry is considered to be of value assessing the usefulness of hearing in the affected ear when evaluating conservation surgery. The use of auditory brainstem responses (ABR) is now relegated to the small number of patients in whom MRI may be contraindicated or not tolerated.

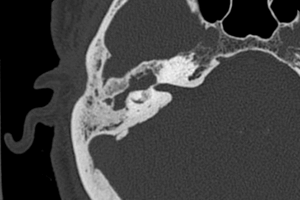

CT scanning has the advantage of being widely available, cheaper than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and it shows bone erosion of the internal auditory canal (IAC) to best advantage. However, MRI is the most accurate diagnostic test for identifying vestibular schwannomas and also has the advantages of multiplanar imaging, of enabling an assessment of the labyrinth, and it does not involve radiation. Thus, it has largely supplanted CT.

There are three management options for estibular schwannomas patients, a course of conservative “watch and wait” management and interval scanning, surgical removal, and stereotactic radiosurgery. The size of the tumor, health of the patient, desire to conserve hearing, and patient preference are the basic factors that should influence treatment decisions. 7.2 The major determinants of which treatment is adopted are: schwannoma size, age, health-status, the desire to attempt hearing preservation, the state of hearing in the opposite ear, and the preference of the patient after due consideration of the advantages and risks of each option.

Stereotactic surgery is considered the first line mode of therapy for small and medium tumors—without signs of brainstem compression.