Dr. Rui Guan interviews Dr. Anthony Reder, an MS specialist at the University of Chicago. This article, geared to residents and fellows, gives insight into Dr. Reder’s world.

About Dr. Reder: Dr. Reder directs the Neurology and Inflammatory Disease Infusion Center at the University of Chicago and is an expert in multiple sclerosis, having written over a hundred papers on the subject.

RG: How did you get into MS?

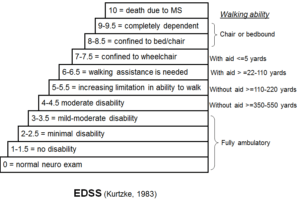

AR: People who get MS are the same age as the residents who take care of them. The average age of onset is at 28. This is a serious disease which gets people in the prime of their lives. So it has a big impact. The important thing now, that was missing during my residency, is that we can actually do something significant for these people and their families.

RG: As a resident working with you, I noted you are efficient but comprehensive. How would you describe your routine in getting ready for clinic?

AR: Caffeine! If I don’t have coffee or tea before clinic, I won’t move as fast. I also learn an incredible amount from my patients. Some have read the world literature on MS and we discuss it. Others describe symptoms with a special nuance that opens up new insights into how the disease affects the nervous system.

RG: Do you read about the patients before clinic?

AR: Absolutely not. In another profession, and profession is truly a term of art for a limited number of occupations, lawyers charge for the time they work with people, plus phone calls, paperwork. and research. Everything they do is compensated. Perhaps that’s the way it should be in medicine too. Many patients have a very extensive records. I prefer to go over the chart with them there in clinic and ask them interactive questions about the data while it is fresh in my mind. I don’t pre-review. If the visit goes over the half-hour or hour limit, then I charge for an extended visit. I complete my notes with the patient in the room, because it is actual time spent the patient’s problems, because more medical questions inevitably come up that the patient can answer, and because it allows reinforcement of therapy plans and clarification of complex and frightening diagnoses.

RG: Did you always used to do this when you were a fellow or a resident?

AR: No! [chuckles] I remember once, as a resident in Minneapolis, when I had a very extensive and complicated history just on one patient. I questioned and listened for an hour, and the mother accused me of not being able to retain it all. But then I generated a 6- page note on this patient with everything they said, because many of us are able to remember everything when we pay attention to important information. With electronic records that don’t reflect my thought processes, and perhaps a busier pace, I don’t have the luxury of sitting under a palm tree and writing my notes.

RG: How would you advise the residents working with you? Can we do our notes while we are in the room with the patients? Does that not disrupt the flow?

AR: It slows you down, which is a problem – the faster you go, the faster an attending could come in [to staff]. But ideally if you could type notes, and have templates of the normal exam which you could enter the aberrations from the norm. It’s just as fast to type them in as to write them, unless you have a cumbersome system where you have to shift fields often with a slow server, like EPIC [chuckles]. Many say the VA’s system is much more user-friendly, and then this would be more efficient for residents too.

RG: Is there anything you are doing much better now as an attending than when you were a resident?

AR: Sleep is important. More sleep means you don’t sleep through rounds. I was always impressed when Drs. Arnason and Noronha were wide awake and thinking the great thoughts, while the residents slept through rounds. Another problem that I avoid is multi-tasking with iPads, phones, and pagers if possible . Once you’re distracted, it’s all over. That brilliant insight or the important fact that you needed for the boards is scrambled.

RG: What are some of your hobbies and interests?

AR: I like running. My son and I go running. I try to keep up with my son, let’s put it that way [chuckles]. He’s in medical school, and I learn a lot from him in this unique physical/mental state. Perhaps it’s the same reason that some people get brilliant ideas in the shower.

Movies. I can apply many of the movies I have seen to neurological problems.

RG: An example please!

AR: I once did morning report and tied 10 different movies to patient problems. There are neurological, social, and behavioral insights from media that deal with the human condition and our frailties. The defense department occasionally calls in Hollywood for insights, so I am not alone.

RG: What projects are you working on?

AR: We are trying to find out how interferon works in conjunction with other drugs and why MS patients live longer when they have been on interferon-beta therapy. In the lab, we are studying interferon signaling and the mechanisms for these important clinical findings.

I am also trying to reverse the societal reallocation of resources to doctors and patients from the current state where money, research effort, and our time has been sucked out of the system by insurance companies, regulations, and a huge bureaucracy. One more reason to charge for my time.

RG: What about phone time with patients?

AR: I do a surprisingly large amount of work on the phone. Many medical interventions should not be done on the phone – like some refills. The doses and durations of treatment can be confused during phone calls. One can run into real trouble by doing this outside of clinic. While it’s easy to sign computer-generated prescription faxes and send them back to the pharmacy, you can easily have patients who have not seen you for years with side effects like falling white counts, tumors, infections, and worsening MS. You are responsible, not the pharmacy computer.

I give a year’s prescriptions if it’s appropriate. If the patient runs out of medicine, that means the year is over, [which] is a long time without medical care, and there has been no clinic visit. This is where the alliance with primary care comes in, to help maintain control of all medical problems and keep an eye on the MS too. With treatment, MS is often a stable disease, so we don’t need to see the patients every 3 months. Last Monday, my first 5 patients had been on treatments for 30-some years, and no one had changed. That would have never been true when I was a resident.

RG: Any closing remarks?

AR: Much of what we do in Neurology involves mechanism and anatomy, that is, how things work. It’s usually not very simple and we have to pay attention to what patients are telling us in the exam room. It’s true with the drugs we prescribe too. They have very complicated mechanisms of action. We often don’t know exactly how the drugs are working. We have theories, but we don’t really know. MS is a complicated disease. Other medical specialties have to generate the whole list of differential diagnoses, but the problems on the bottom of the list are rare events. In Neurology it’s not simply an ear infection, it’s herpes zoster of a cranial nerve or an acoustic neuroma.