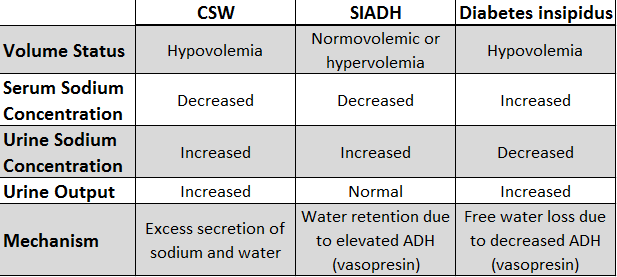

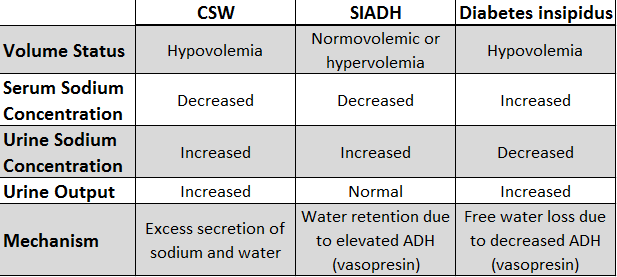

Both cerebral salt wasting and SIADH (sometimes both together) are commonly found in patients with intracranial hemorrhages. Differentiating between the two has important clinical implications, since the interventions are different for each syndrome.

ADH

To briefly review, ADH (anti-diuretic hormone, or vasopressin) is primarily produced in magnocellular neurosecretory cells of the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus, transported to the posterior pituitary gland, and secreted when hypothalamic osmoreceptors sense high serum osmolality – usually 280 or greater. Increased plasma osmolality is the main stimulus for ADH secretion, with maximum secretion at osmolality of approximately 295. ADH works primarily at the level of the renal collecting duct and distal convoluted tubule, facilitating water reabsorption through aquaporin channels. ADH also increases peripheral vascular resistance and arterial blood pressure.

SIADH

Syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion (SIADH) is often seen in the context of CNS disease, such as days 3-14 following sub-arachnoid hemorrhage, and is likely related to hypothalamic dysfunction. SIADH can also arise in the setting of neoplasia (ex. small-cell lung cancer), non-neoplastic pulmonary pathology (ex. TB), and as a drug side effect (ex. SSRIs, carbamazepine), to provide a few examples.

In SIADH, ADH secretion cannot be suppressed, free water is inappropriately retained, and plasma sodium decreases by dilutional effect. Further, increased plasma volume is sensed at the level of the kidney’s juxta-glomerular apparatus, which decreases secretion of renin, inhibiting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and ultimately increasing Na+ loss in urine, along with some free water. Therefore, in SIADH, patients are usually noted to be hyponatremic but either euvolemic or mildly hypervolemic. Urine sodium is generally >40 mEq/L in SIADH, greater than expected for the low serum sodium concentration.

In the case of subarachnoid hemorrhage, patients are often given significant amounts of fluid hydration in order to preserve CPP – which could contribute further to any dilutional hyponatremia occurring with SIADH. Hyponatremia ([Na+]<135 mEq/L) increases the risk for cerebral edema, as the osmotic gradient creates a volume shift to the intracellular environment. Mild hyponatremia (125-135 mmol/L) is often asymptomatic; moderate hyponatremia (115-125 mmol/L) is accompanied by symptoms such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, personality changes, lethargy, and muscular irritability; and extreme hyponatremia (<115 mmol/L) may result in obtundation, seizures, and death. Rapid changes in serum osmolality are associated with higher-risk outcomes, such as central pontine myelinolysis.

Diagnosis of SIADH should include rule-out of other possible reasons for high ADH secretion, including true volume depletion via GI or renal losses, in which case the patient is likely to be hypovolemic; decreased tissue perfusion due to low cardiac output or cirrhosis, in which patients are likely to be hypervolemic; and “reset osmostat,” an SIADH variation explained below. Cerebral Salt Wasting (CSW) should also be considered as a possible etiology, as it is also seen in the setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage, and its clinical management is different than SIADH. Finally, inappropriate ADH secretion can occur as a result of renal, adrenal, or thyroid dysfunction, and so those etiologies should be ruled out if suspected.

Reset Osmostat

“Reset osmostat” occurs when the threshold for ADH is lowered due to regulatory dysfunction, such that ADH is secreted when plasma osmolality is less than 280 mosm/kg, resulting in mild hyponatremia (125-135 mEq/L). Osmoreceptors function effectively with their new threshold, such that supplementation of the patient with salt or hypertonic solutions will stimulate thirst in the patient. Management of this condition is often focused toward treating the underlying disease.

Cerebral Salt Wasting (CSW)

CSW presents similarly to SIADH, with hypotonic hyponatremia and high urine sodium, usually within 10 days of neuronal trauma; for example, it has been reported in 7-23% of cases of aneurysmal sub-arachnoid hemorrhage. However, as opposed to SIADH, in which inappropriate ADH secretion leads to transient volume retention followed by a correctional sodium loss, in CSW, salt wasting is the primary defect, followed by volume loss and subsequent baroreceptor-stimulated ADH release.

There are two main proposed mechanism for this disorder: in the first, disruption of sympathetic input to the juxtaglomerular cells of the kidney impairs the normal response to volume depletion, such that the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is not triggered, and Na+ and free water are inappropriately excreted in the urine. The second hypothesis is that in the setting of neural injury, a systemic factor is released to inhibit renal tubular sodium reabsorption, lower plasma volume, and possibly protect against increased intra-cranial pressure. Candidate substances include brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP). BNP lowers sodium reabsorption and inhibits renin release, and it also has vasodilatory properties, which have been thought to decrease vasospasm in subarachnoid hemorrhage. To support this proposal, one prospective observational study found that patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage had increased urine volumes and sodium excretion, correlating with increased plasma BNP, increased ICP, and lower aldosterone levels, as compared with control patients undergoing craniotomy for tumor resection.

Of note, some researchers argue that CSW is not a real phenomenon, but rather a misinterpretation of patients’ appropriate sodium excretion following administration of the IV fluids – or possibly a normal consequence of decreased venous capacitance following catecholamine-induced vasoconstriction. Yet many believe that CSW is a real phenomenon, separate from SIADH. In both conditions, patients will be hyponatremic, with elevated urine osmolality; however, SIADH patients are either euvolemic or hypervolemic, while CSW patients are hypovolemic, and each groups responds differently to therapy.

Treatment

This distinction guides management. Therapy for CSW includes volume repletion with isotonic saline and oral salt replacement for the duration of symptoms, usually 3-4 weeks. Adequate volume repletion will remove the stimulus for ADH secretion, resulting in dilute urine. In contrast, SIADH is treated by fluid restriction – except in patients with conditions like subarachnoid hemorrhage, for whom fluid restriction poses the risk of cerebral infarction. Such patients require administration of hypertonic saline with electrolyte concentration greater than excreted concentration in urine. Infusion of isotonic saline in the case of SIADH will worsen hyponatremia, since it will trigger increased sodium excretion, with some retention of free water, and thus continued hyponatremia. It must be noted that SIADH and CSW may coexist within a single patient, complicating treatment strategy.

Overall, the goal of treatment for SIADH is normovolemia and normonatremia, with avoidance of any osmolality change greater than 8 mEq/24 hours. Relatedly, studies have shown that treatment with mineralocorticoids within a few days of aneurysm rupture can improve natriuresis and hyponatremia.

Sources

Palmer B. Cerebral Salt Wasting. In UpToDate, Sterns, R (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2013.

Rabinstein and Bruder. Management of Hyponatremia and Volume Contraction. Neurocrit Care 15:354-360, 2011.

Rahman and Friedman. Hyponatremia in Neurosurgical Patients: Clinical Guidelines Development. Neurosurgery 65(5): 925-932, 2009.

Ramachandran et al. SIADH. Lorincz M, editor-in-chief. MedLink Neurology. San Diego: MedLink Corporation. Available at www.medlink.com. Last updated: May 3, 2012.

Sterns et al. Pathophysiology and etiology of the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH). In UpToDate, Emmit, M (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2012.