Migraine headaches are one of the primary causes of analgesic abuse. Neurogenic peptides, such as serotonin and dopamine, have been increasingly implicated in their origin. Apparently, these vasoactive neuropeptides stimulate an inflammatory cascade that includes the release of endothelial cells, mast cells, and platelets. Serotonin receptors are thought to be the most important receptors in the headache pathway.

Initial migraines may occur in childhood, and there are some who feel that childhood migraine is the most common cause of childhood headaches. Migraines will typically continue through patients’ 30s and 40s but rarely continue beyond age 50. Any “migraine” after the age of 55 should be evaluated for intracranial pathology.

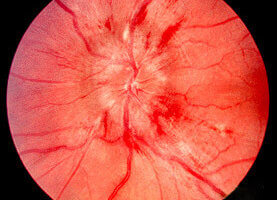

Aura occurs in 20% of migraine patients although it is generally considered to be far more common. The syndrome of aura may begin days or hours prior to the actual headache. Visual aura are the most common and may take the form of scotoma—blind spots, fortification—zig-zag patterns, and scintilla—flashing lights. Other neurological aura include unilateral paresthesias, unilateral weakness, hallucinations, and hemianopsia.

The headache itself is most commonly unilateral—60% to 70% of the time. It is also most commonly throbbing or pulsatile, but roughly half of migraines evolve into a constant dull ache. The headache typically lasts from 4 to 72 hours. Accompanying the headache are the symptoms of nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, and lightheadedness.

National guidelines emphasize accurate diagnosis as beginning any appropriate treatment regimen. Part of the history should be a detailed and accurate history of previous and current treatments, bearing in mind that both prescription and OTC products have the potential for exacerbating underlying headache patterns. Since these headaches can be incapacitating, chronic, and involve the head and neck. National guidelines define a five step program to include identifying components of migraine symptomology that allow for intervention as early as possible in the migraine process, selecting the best pharmacologic options for each patient, instructing patients in the proper use of their medications, encouraging use of a headache diary to monitor treatment and medication usage, and providing information resources for patient education.

Treatment must be individualized, based on factors that include pain intensity, degree of disability, comorbidity, presence of nausea and vomiting, previous treatment(s), and patient preferences. Treatment may need to be individualized for specific attacks as well. Patients benefit from a stratified approach, with mild to moderate attacks being treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or combination analgesics, such as aspirin plus acetaminophen plus caffeine, or acetaminophen plus isometheptene plus dichloralphenazone, and headaches that are more severe being treated with migraine-specific medication such as triptans or ergotamines.

Non-oral triptan or dihydroergotamine (DHE) with or without an antiemetic is effective if administered early in those circumstances where headaches appear to be escalating rapidly or are accompanied by nausea or vomiting. Further individuation is possible with regard to formulation and route of administration. Non-oral routes and the addition of anti-emetics used for nausea; injections used for faster administration; and in the intermediate circumstance, suppositories and nasal sprays.