Acute vision loss may be caused by central retinal artery occlusion, central vein occlusion, temporal arteritis, optic neuritis, optic neuropathy, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, neovascular age-related macular degeneration, stroke, hysterical conversion reactions, or malingering. Acute vision loss may last minutes or hours, amaurosis fugax. Causes of this entity include ocular migraine, emboli to retinal arteries, and transient ischemic attacks.

Central retinal artery or vein occlusion, embolus, ischemic optic neuropathy, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, or optic neuritis can all cause sudden vision loss in one eye. Optic neuritis is often accompanied by pain with eye movement. Painful loss of vision in one eye can be caused by acute closed-angle glaucoma, uveitis, or, rarely, corneal hydrops.

The so called “curtain” or “window shade” being drawn in one eye is usually caused by retinal detachment or a progressive vasculature problem, such as branch retinal artery occlusion.

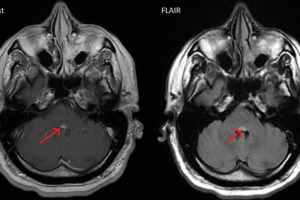

Migraine headaches cause shimmering or flashing lights (scintillating scotoma) that obscure vision in both eyes. When this phenomenon clears it may then be followed in roughly 20 minutes by the migraine headache. However, the scotomata may occur without a subsequent headache in what is termed a migraine equivalent. Bilateral visual field loss, sometimes with neurological symptoms, that lasts less than 24 hours, suggests a transient ischemic attack of the visual cortex. Such an event that lasts longer than 24 hours is probably due to a stroke.

Historical data that are important when examining patients with sudden vision loss include whether one eye or both eyes affected (be sure to differentiate between one sided vision loss and visual field loss), history of trauma, prior episodes, a general ophthalmologic history, presence of preceding photophobia, headache, pain, and any history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, collagen vascular disease, hematological disorders, cancer, or drug usage.

When examining the patient, first note the external appearance of the eye—whether it is red and injected and whether there are any extrinsic abnormalities. Then check for visual acuity, light or movement perception, extraocular movements, pupil reactivity. If possible, do a slit lamp exam, with and without fluorescein staining. Inspect the cornea and conjunctiva for edema, scarring, infection, keratopathy, and ulcers. Intraocular pressure must be measured.

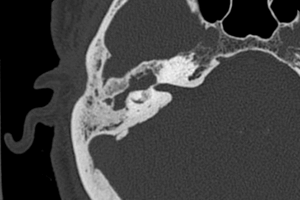

With an ophthalmoscope, check the anterior chamber for hyphema, cells and floaters. The fundus should be checked along with its disc with careful attention to signs of pressure or retinal detachment. In this case, the retina appears gray and detached.

There are tricks that can be used to evaluate for hysterical vision loss. One of these is to double the distance between a patient and the visual field chart. This should double the size of central vision— in hysterical patients, the central visual field remains the same. Another tool is an optokinetic drum. This stimulates nystagmus if the eye is recording an image. Finally, moving a mirror close to a patient’s face will make a patient’s eye move if vision is present.

A full cardiac, neurologic, and head and neck exam should also be performed. Particular attention should be given to the presence of cranial nerve abnormalities, muscular weakness, temporal artery tenderness, sensory abnormalities, murmurs and carotid bruits.

Embolism is perhaps the most common cause of acute vision loss. Emboli are the most common cause of amaurosis fugax—the brief vision loss. If an embolus resolves, the “curtain” appears to rise, the “fog” clears.

Cholesterol emboli, or Hollenhorst plaques, can also cause strokes and appear as shiny, golden spots. These usually come from carotid arteries. Calcific emboli appear as grey-white blobs at or near the optic disc and usually come from valvular lesions.

Temporal arteritis is one of the few ophthalmologic emergencies. Any elderly patient with a transient visual loss must have this entity in the differential diagnosis. If not treated immediately, it can rapidly progress to bilateral blindness from arterial occlusion or ischemic optic neuropathy.